I have never been the kind of Bruce fan who has seen every concert. I haven’t played every one of his albums non-stop, nor do I know every small detail about his life and work. There are those kinds of fans. I know those kinds of fans. The truth is, I was just never on the ball enough to get that kind of shit together. Obsessive details are not my strong suit. I did grow up listening to Bruce, as I grew up listening to Bob Dylan – almost to the exclusion of everyone and anything else. I’d be lucky if some great guy would deposit a mixed tape in my life and open up a world of music to me. That happened a lot. It wasn’t that I was always the girl who loved the music the guy loved. It was that the men I loved or even liked a lot usually had better taste in music than I did and so they would introduce it to me. Listening to it through them, as though I WAS them, was how they entered me so profoundly, for many years. As such, music is often tied to a relationship, for better or worse.

But Bruce was a standalone love, not tied to anyone in particular. He is so universal that if he touches you deeply he becomes a part of you and a part of your life forever.

His Broadway show, which I should have moved mountains to pay thousands to see but didn’t, is one of the best things I’ve ever seen him do. He tells stories – Bruce stories in the way he tells them, just not the way we expect to hear them. He doesn’t want to bring us to heightened excitement so much as sit around the fire and tell us a few tales. It turns out they are all quite moving. His story about his mother, Clarence, his father, his hometown.

We know these characters because they thread throughout his songwriting, inspire so many of the lyrics – the universe of Bruce and New Jersey and working class men and women trying to find a reason to believe. Bruce has taken us all the way there, like his own private Idaho, or his Castle Rock. I know Faulkner has one too but I can’t remember what it’s called.

The way I listen to Bruce now is only through his live recordings. I can’t listen to the original records because I’ve heard them too many times. On the Netflix show, as many times as I’ve heard Born to Run, it sounds different when sang as part of a storytelling ceremony, though the eternal power of that song is unbreakable.

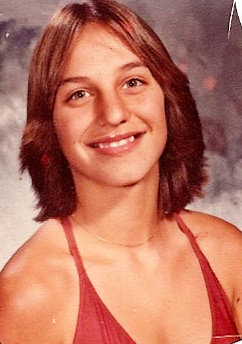

I was a teenager when I first was deeply touched by Bruce. Darkness on the Edge of Town was my favorite – a record full of longing, full of desire for something you don’t have yet – which is, a life somewhere else. I remember listening to it in my bedroom over and over, Something in the Night, Prove it All Night, The Promised Land, Candy’s Room, Racing in the Street. The whole thing, like so many of his albums, has a distinct beginning, middle and end – it’s designed with its own dramatic arc, with conflict, and Bruce always feels the impulse to right things in the end. He doesn’t want to send you away sad.

The best lifelong songwriters do compile their albums to be long stories that take you from one place to another. Springsteen is particularly good at the highs (no one does the highs better, no one) and the lows. In his show on Netflix he talks about going on a journey with his fans, and how performing for us gave him a profound sense of purpose. He thanks all of us for going on that journey with him. Oh, how many of us want to thank him for filling the empty spaces, for reviving dead things, for taking us into worlds of used cars, wet skin by rivers, Jersey girls, velvet rims, state troopers, forgotten wives, redheaded women, the badlands, ghosts of Tom Joads, brilliant disguises, men who wrestle with demons, women who try to stand by them and love them. How do we thank someone who has given us all so much?

Maybe we can thank him by remembering what the real stuff is, by staying connected to people creating music and worlds still, in this blacked out, empty, dark and lonely world. We can keep what Bruce helped invent alive. Maybe that will matter. Maybe.

I spend way too much thinking about me.

This is the blank space where that paragraph should be.

I spend way too much thinking about me.

This is the blank space where that paragraph should be.